Have you ever experienced gas, bloating, cramping, diarrhea, constipation, or blistery dermatitis on an ongoing basis? Have you ever suffered from a persistent illness, yet medical tests were inclusive or found “nothing wrong with you”?

If this sounds familiar, you’re not alone — for millions of people, that’s the agonizing reality of their everyday lives.

Here’s another question: Have you ever noticed that your symptoms improve or get worse depending on the foods you eat?

If you answered “yes,” you may have what’s known as a food intolerance. But that’s not the same thing as a food allergy (we’ll explore the differences soon). However, just as food allergies have been on the rise, the incidence of self-reported intolerances seems to be increasing, as well. According to a 2019 article published in the journal Nutrients, food intolerances now affect up to 20% of the population. That’s a lot of people, many of whom could alleviate their suffering and be much happier if they knew about — and could therefore choose to avoid — the foods that trigger their symptoms.

In this article, we’ll look at three of the most common food intolerances, what science says about their potential causes, how you can determine if you have one, and steps you might take to alleviate uncomfortable symptoms.

What Is a Food Intolerance?

A food intolerance is a negative reaction to a food you’ve eaten. (No, I don’t mean, “Man, those flavors are nasty” — we’re talking about physical symptoms here.) Food intolerances are different from food sensitivities and allergies, although they’re sometimes lumped together.

Food sensitivities and allergies are usually due to an immune response to a certain food — basically, the immune system mistaking it for something harmful. That triggers a host of systemic reactions that can include hives, swelling of the face and throat, and difficulty breathing. Food allergy symptoms typically occur immediately after consuming the offending substance.

Food intolerances, on the other hand, don’t usually involve the immune system. They are due to an inability to digest or metabolize a certain food or component of food — often (though not always) a carbohydrate. Symptoms of food intolerance usually begin anywhere between 30 minutes to two days after eating or drinking the food in question.

Food intolerance symptoms are usually dose-dependent, meaning you may be able to eat limited amounts of the food in question without triggering symptoms. This is very different from food allergies, where even trace amounts of the triggering food are potentially dangerous.

Despite the delayed symptoms and the relatively low, short-term health risks associated with food intolerances, living with them is no picnic. Over time, the risks can increase, as the intolerances may trigger digestive health complications such as gas, bloating, cramping, and diarrhea, along with fatigue, headaches, or skin irritation. Food intolerances and sensitivities are sometimes seen in conjunction with other health concerns like IBS, autoimmunity, and endocrine issues.

Common Types of Food Intolerances and Potential Causes

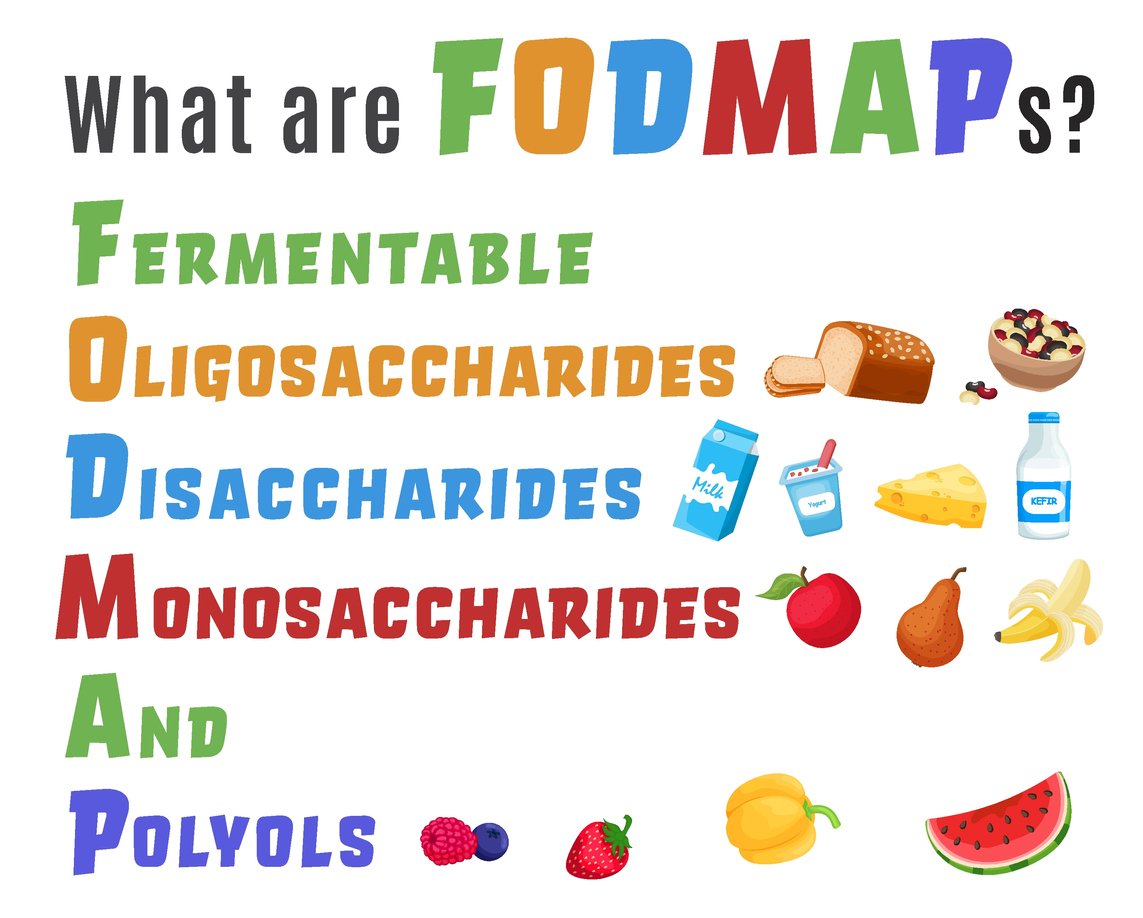

While food intolerances can develop around any food or food-like compound (including food additives), some intolerances are more common than others. Here we’ll take a closer look at three of the most frequent food intolerances: lactose (found in milk), gluten (found mainly in wheat, barley, and rye), and FODMAPs (fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols — more on that later).

Lactose Intolerance

Milk products contain lactose, which is a sugar carbohydrate. In order to digest lactose, we need to produce the digestive enzyme lactase. And, especially after infancy, not everybody produces much, or any, lactase.

Symptoms of lactose intolerance usually develop over time and can include bloating, diarrhea, and gas. Many people who eat dairy regularly suffer from these symptoms and have no idea that dairy products are the cause of their discomfort.

For people with lactose intolerance, it’s usually best to avoid foods that contain cow- (and often also goat-) based dairy products, including things like cow’s milk, ice cream, yogurt, and cheese. But milk is a prevalent ingredient in many types of foods. Food Allergy Research and Education (FARE) offers an in-depth list of dairy products to avoid if you suffer from a milk allergy — and the list also helps if you’re avoiding dairy for lactose intolerance, or for any other reason.

Thankfully, it’s easier than ever to avoid milk and dairy products thanks to the growing availability of plant-based options. Here are some exciting dairy alternatives to try:

What Causes Lactose Intolerance?

Most infants can digest lactose (which is a very good thing, since the only menu item for most babies, breast milk, contains about 7% lactose), but at some stage of childhood or even adulthood, many people cease producing lactase and develop what’s generally called lactose malabsorption. Experts estimate that about 68% of the world’s population has lactose malabsorption. (Given how common this is, it’s kind of weird to give it a name that makes it sound like a disease, as if it’s abnormal somehow.)

According to various studies, lactose malabsorption is most common in people of African, Hispanic, and Asian descent. The current USDA MyPlate recommendations are a significant improvement over previous iterations, as they incorporate individualized portion sizes and allow for some non-dairy alternatives. However, in the US, dairy foods are still subsidized and heavily marketed as healthy for everyone — regardless of their racial background and lactose absorption status. Critics of the food system decry the negative health impacts of this approach on the ethnic groups that are most impacted by it — all of whom are people of color.

It makes sense, if you think about it, that many humans would cease to produce lactase as they grow up. Most of us don’t have any need for mother’s milk after the age of three or four. In fact, modern humans are the only species of mammal that drinks milk after infancy — and we’re also the only species that drinks the milk of another species.

Milk Is Designed for Baby Cows

Much of the dairy consumed by humans is cow’s milk — a food made for baby cows. Importantly, baby cows have very different digestive systems and growth needs than humans.

Cows are ruminants with four-compartment stomachs that are quite distinct from our own. Cow’s milk is also very different from human milk and is much higher in protein and saturated fat than human milk. The composition of cow’s milk enables calves to gain more than 600 pounds in their first year of life. (Trivia time! The average Holstein weighs 82 pounds at birth and around 700 pounds at 12 months. If a 7-pound human baby grew at the same rate, how much would it weigh on its first birthday? The answer is 60 pounds! Can you imagine a 60-pound one-year-old? Parents have a tough enough job without having to become weightlifters just to change a diaper!)

The point, of course, is that human milk is more well adapted for slower growth and optimal human brain development.

So what about sheep’s and goat’s milk? Like cows, sheep and goats are also ruminants with distinct digestive and growth needs from humans. But some people may have an easier time with milk from these animals because it contains less lactose.

Non-Celiac Gluten Intolerance

Gluten is a protein found in certain types of grain and their derivatives. Research from the Center for Celiac Research at the University of Maryland estimates that approximately 6% of the US population may have a gluten intolerance.

Gluten intolerance is not to be confused with celiac disease, which is an autoimmune disease, where the body attacks itself in the presence of gluten. It’s also quite different from a wheat allergy — which is a true allergy to grains in the wheat family, not necessarily all gluten-containing grains.

Symptoms of gluten intolerance can include:

- Bloating

- Gas

- Brain fog

- Abdominal pain

- Changes in bowel movements, anywhere from diarrhea to constipation

- Joint pain

- Muscle cramps

- Neuropathy

- Skin rash, particularly on the hands and fingers

Foods to avoid if you have a gluten intolerance include wheat, rye, barley, and triticale — and food products made from them.

Importantly, in addition to wheat berries and flours, people with a gluten intolerance also need to look out for other forms of wheat, which include durum, emmer, semolina, spelt, farina, farro, graham, KAMUT® Khorasan wheat, and einkorn. Buckwheat does not contain gluten (don’t be alarmed by the name — it’s unrelated to wheat, actually being in the same botanical family as sorrel and rhubarb) and is safe to eat if processed in a gluten-free facility.

Wheat or wheat products are very common food ingredients, particularly in processed foods like bread, pasta, baked goods, sauces, cereals, soups, roux, salad dressings, soy sauces, beer, malt, malt extracts, malt vinegar, food coloring, and brewer’s yeast (unless they’re certified gluten-free).

So, what can you eat if you are intolerant to gluten? Gluten-free foods have come a long way in recent years. You can buy gluten-free whole grains or look for gluten-free varieties of the above-mentioned foods. Plus, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and seeds are obviously free from gluten as well. I’ve even seen bottled water advertised as “gluten-free” (which tells me that bottled water marketers are really struggling to say anything new and meaningful about their product).

For our article on healthy, gluten-free breads that taste amazing, click here.

For more on gluten intolerance, see our article, here.

What Causes Gluten Intolerance?

The exact cause of gluten intolerance is not well understood. Research by Armin Alaedini, an immunologist at Columbia University, found that, when compared with both healthy people and those with celiac disease, some patients who suffered from symptoms of gluten intolerance had significantly higher levels of a certain class of antibodies against gluten. This appeared to suggest a short-lived and systemic immune response.

According to Alaedini, the finding hinted that the barrier of those patients’ intestines might be disturbed, allowing partially digested gluten to get out of the gut and interact with immune cells in the blood. And indeed, when 20 of these patients spent six months on a gluten-free diet, their blood levels of those markers declined.

But gluten intolerance can still be difficult to understand. Symptoms are sometimes not reproduced in double-blind food challenges, suggesting a placebo effect or non-gluten physiological effect — at least in some cases. Evidence also suggests that, for some people, it may not even be the gluten itself causing a reaction.

As researchers look beyond gluten, other possible culprits of gluten intolerance could be:

- Fructans, part of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides, and polyols (FODMAPs, which we’ll get to next)

- Amylase trypsin inhibitors (ATIs, or wheat proteins that may protect the plant against pests)

- Wheat germ agglutinin (WGA, another protective wheat protein)

- Glyphosate (an herbicide that’s often sprayed on non-organic wheat crops as a desiccant, to dry the crop out before harvest)

Hinting that something beyond gluten may be at work here, many Americans self-report that they can eat gluten-containing foods in Europe and elsewhere without complications. This may be due to the type of wheat or how the wheat was grown or treated. Glyphosate, in particular, is being looked at as a possible driver for the rise in gluten intolerance and celiac disease because of its widespread use in conventional food production, and its tendency to disrupt the human gut microbiome.

FODMAP Intolerance

FODMAP stands for Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Monosaccharides, and Polyols (phew, I’m really glad they went with the acronym for it). These are all different types of short-chain carbohydrates that are fermented by your gut bacteria — and that are poorly absorbed by some people.

While this is not a problem for most, it can cause symptoms for those with especially sensitive digestive tracts. FODMAP intolerance is sometimes mistaken for gluten intolerance, celiac disease, or lactose intolerance because there is some overlap of foods and symptoms. If you suffer from IBS, FODMAP intolerance is worth looking into as it often presents with an IBS diagnosis. In fact, the leading dietary recommendation for people with IBS is a low-FODMAP diet, because these foods can trigger IBS-associated symptoms like diarrhea, constipation, gas, bloating, indigestion, nausea, and vomiting.

Unlike other food intolerances where it’s sometimes recommended to completely avoid triggering foods, with a FODMAP intolerance you may not want to completely avoid the foods that contain them. In fact, many FODMAP foods are highly nutritious, and total avoidance could cause nutritional deficits. A low-FODMAP diet, where you limit the amount of food you consume to avoid symptoms, is usually a temporary measure to pinpoint the exact foods that are causing you discomfort.

Many foods contain FODMAPs, but they roughly fall into these categories:

- Gluten-containing grains

- Allium vegetables — like onions and garlic

- High-fiber fruits and vegetables — like cabbages and apples

- Legumes

- Mushrooms

- Sweeteners — like maple syrup, molasses, or honey

- Candy and soft drinks

What Causes FODMAP Intolerance?

The exact cause of FODMAP intolerance is unknown, but it’s widely thought to be related to an imbalance in gut bacterial communities — or “dysbiosis.”

Many lifestyle and environmental factors can fuel dysbiosis, including stress, infections, antibiotics, pesticides, processed foods, and a lack of prebiotic fiber.

Fiber feeds the good gut bacteria, and without it, the “bad guys” can overtake the good, wreaking havoc on your digestive system and your health.

Because many high-FODMAP foods contain the fiber necessary to feed good gut bacteria, a low-FODMAP diet is only recommended temporarily to identify specific dietary triggers. Long-term use of an across-the-board low-FODMAP diet can actually make gut symptoms worse.

To address the underlying symptoms associated with FODMAPs, it can help to work on strengthening gut health and slowly increasing fiber intake over time. If you’re exploring FODMAPs for your gut health, check out the book Fiber Fueled by Dr. Will Bulsiewicz, who offers further guidance on dealing with these foods and reclaiming your gut health. (Spoiler alert: Dr. B views the gut as a muscle. You can strengthen a weak gut through regular and titrated exposure to challenging foods, just as you can strengthen a weak muscle by regular and titrated exposure to weights. But you don’t want to overdo it, especially when you’re starting out — or you could risk injury.)

What Can You Do if You Suspect a Food Intolerance?

Food Intolerance Testing

Testing for food intolerances is difficult. Blood tests like IgG antibody tests can measure the immune response to foods, which can be helpful in diagnosing food allergies. But when it comes to food intolerance diagnosis, they are prone to a lot of “false positives” and are generally not recommended.

You can do a hydrogen breath test to determine if there’s bacterial overgrowth in the gut or an intolerance to lactose, fructose, or sucrose — but the usefulness of that information really is still a matter of debate. So ultimately, the best way of diagnosing a food intolerance is to monitor your symptoms and the foods you eat.

Keeping a Food Diary

If you think you may have a food intolerance or sensitivity, keeping a food diary is one way to develop some objectivity. To keep a diary, you should write down what you eat and drink for each meal and snack, followed by any gastrointestinal symptoms during or after eating. (Starting with “Dear Diary” is totally optional.) After several days, you may start to observe patterns for when you experience symptoms and when you don’t. If you have questions about how to interpret your results, a health care professional or dietitian may be able to help you better understand your food diary and recommend next steps.

To get you started, we’ve put together a sample food diary you can download for free, here.

Starting an Elimination Diet

Because intolerances to food are different for every person, are difficult to diagnose, and symptoms may not appear for hours or days, it can sometimes be easier to pinpoint troublesome foods by removing and then methodically reintroducing them. In fact, elimination diets are usually the best way to determine a food intolerance.

During an elimination diet you eat very simply, with meals free from common food triggers, until your symptoms resolve. While everyone is different and your elimination diet will be unique, many people focus on eating clean, whole foods to ensure they are not accidentally ingesting a trigger food.

The elimination protocol can take from three to five weeks, sometimes more, to complete. If symptoms resolve, then you can slowly and carefully reintroduce foods, one at a time, based on what you think you may be able to tolerate — and if you experience the return of the problematic symptoms, then whatever you have recently reintroduced becomes a likely suspect.

So, what foods should you eliminate with this kind of diet? There are different types of elimination diets and schools of thought as to how to go about them. In general, there are four main steps to an elimination diet:

- Planning and preparing

- Eliminating

- Challenging

- Creating a new diet

Here is a helpful example of a plant-based elimination diet.

Importantly, not everyone is the same in how they react to different foods, and individualized plans are necessary. It’s often best to work with a nutritionist or health care practitioner to determine what kind of elimination diet you should try and for exactly how long.

In Conclusion

Food intolerances are widespread and increasingly common. Unlike food allergies or sensitivities, intolerances generally don’t trigger an immune response and are mainly gastrointestinal in nature. Depending on the type of intolerance you may have, there are changes you can make to help you deal with your food intolerance and alleviate symptoms. For any of them, consider eliminating potentially problematic foods, and working to heal your gut. In the case of FODMAPs and even gluten-containing grains, you might be able to reintroduce these foods to your diet someday — after a break, and after your digestive tract has become more resilient.

Tell us in the comments:

- What is your experience with food intolerances?

- Have you ever tried an elimination diet? How did your diet change as a result?

- Do you think you’ll try to identify any food intolerances?

Featured Image: iStock.com/Piyapong Thongcharoen