Take the 101 South out of San Francisco through Silicon Valley, past the campuses of Apple, Google, and Facebook. You’ll drive past Whole Foods Markets, Trader Joe’s, Costcos, Walmarts, medical centers, golf courses, fruit stands, and farmers markets. Continue south, hang a left at Gilroy, and hit CA-152 West. As you pass the San Luis Reservoir and Recreation Area, you’ll see signs warning prospective swimmers and boaters to avoid the water due to toxic algal blooms.

The 152 rolls into Highway 99 as you continue through Fresno and finally reach your destination, the small town of Dinuba, California. You’ll find yourself at the base of Smith Mountain, smack dab in the center of the San Joaquin Valley.

Around 66 million years ago, the Pacific Ocean was having trouble deciding how big it wanted to be. Over the next 60 million years, the San Joaquin Valley was repeatedly flooded with ocean water as the sea level rose and fell. Then, thanks to some tectonic friskiness, the coastal ranges were lifted to the point where the ocean could no longer breach them on a regular basis. Two million years ago, the glaciers flowed through, converting the sediment-rich valley into a giant freshwater lake.

To the naked eye, that lake is gone — but if you had X-ray vision, you’d see that it’s just moved underground, creating a giant freshwater aquifer. The fertile soil, watered by the remaining lakes, rivers, streams, and springs were more than enough to support several indigenous peoples, including the Yokuts and Miwok, who hunted, foraged acorns, berries, and pine nuts, and even cultivated tobacco.

Over the past 50 years, the San Joaquin Valley has become the most important agricultural land in the US, producing the majority of the crops grown in California, which itself provides almost 13% of the nation’s total.

How Small Farms Are Impacted By Agricultural Water Usage

Today, you’re here to meet Rebecca and Tory Torosian, who own and run Tory Farm in the San Joaquin Valley, a small citrus and stone fruit farm that’s been providing healthy and delicious produce to their community for over five decades. The pride and joy of their operation is the five acres of orange, mandarin, and grapefruit, especially their prized oro blanco (“white gold”) variety.

I mean, those orchards were their pride and joy.

Faced with a worsening statewide drought, their irrigation district cut off their water supply, which they had received via a canal from the nearby Kings River. At first, they thought they might be able to save their citrus groves by watering them from the wells on their property. But small farms can’t afford to dig deep wells. And the Torosians found that they could draw only a fraction of the water needed to keep the trees alive. Not only that, the extra energy required to operate the struggling pumps increased their electricity bill by 30%.

As a result, they’ve had to make the tough decision to abandon the citrus orchards in order to save their apricot, peach, plum, and pluot groves. Whether they or the other 70,000 small farms that make up the beating heart of California’s agricultural economy will survive is now in serious doubt.

Meanwhile, what happened to all that water? Sure, there’s been a historic drought, which hasn’t helped matters. But that’s what groundwater is for, to keep the people and farms alive until the rains return.

Unfortunately, the lion’s share of the groundwater isn’t going to the farms that provide us with healthy and delicious plant foods. While the Torosians steward their dwindling water supply drop by drop – and lawmakers urge California residents to replace their lawns with cacti and stones, install low-flow shower heads, and only flush their toilets when truly needed – other agricultural sectors in the region are awash in freshwater. And those sectors have one thing in common: they all go “moo.”

Freshwater Is in Decline

The problem is global. Water covers 70% of our planet. But despite the fact that we live on “the water planet,” the reality is that fresh water — the stuff we bathe in, drink, and irrigate our farms with — is remarkably scarce. It makes up only about 3% of the world’s total water supply. (And I’m not just worried because my name is Ocean. My son River shares my concern, too.)

Every day on this planet, there are more people. But the global supply of freshwater is in decline. In fact, the available freshwater resources per person have declined by more than 20% over just the past two decades.

The largest consumer of water worldwide is agriculture. But certain foods and dietary patterns have a much larger water footprint than others. If the rest of the world ate like Americans — consuming large quantities of meat, eggs, and dairy products — the planet would have run out of freshwater 15 years ago. Even executives from Nestlé, the world’s largest food company, privately told US officials that the world is on a collision course with doom because non-Americans are now also eating too much meat. (It took Wikileaks to reveal this information, which was documented in a secret US government report.)

Why is agriculture putting such a drain on our water? How do different foods measure up when it comes to water usage? And how can you make an impact by choosing what you put on your plate? Let’s take a closer look.

The Link Between Agriculture and Water

Currently, agriculture accounts for 70% of global freshwater consumption. Some of this is direct use — like watering crops and providing drinking water for animals. And some is indirect – like the water used in the production of feed, fertilizers, and pesticides.

The problem isn’t that we’re using water, but that we’re overusing it. The world’s supply of usable water is finite (and it doesn’t look like we’ll be mining outer space for H2O anytime soon).

But industrial civilization, in general — and industrial-scale agriculture, in particular — has ignored this constraint, choosing instead to draw down Earth’s water inheritance: groundwater.

Groundwater Overuse

Groundwater is what it sounds like: water that’s under the ground, rather than the stuff that falls from the sky, or exists above ground in rivers, lakes, streams, glaciers, and so on. Immense underground aquifers store water that has been purified through long and winding journeys from the sky through the soil. It’s precious stuff.

About 140 million residents of the US, and more than 2.5 billion people worldwide, depend on groundwater for their water supply on a regular basis.

Unfortunately, increased demands placed on our groundwater resources have overstressed aquifers in many areas of the world. More than three billion people live in areas with significant water shortages. And agriculture is the leading cause of groundwater overuse or depletion, which is what happens when water levels decline because of sustained groundwater pumping.

Effects of Groundwater Depletion

In addition to reducing the amount of life-giving water available, the effects of groundwater depletion include:

- Lowering of the water table, which can reduce the amount of available water for all uses

- Land subsidence, which is a fancy term for the shifting, compacting, and degradation of land (including land on which buildings sit) due to the overuse of water from underground aquifers. (Imagine all these buildings resting on a giant waterbed, and picture what happens when the water is slowly pumped out.)

- Water contamination, largely from the threat of saltwater intrusion (basically, when oceanic salt water enters areas of fresh water because the fresh water reserves are so low)

- Higher costs and energy usage, because water has to be lifted higher to reach the surface, which often requires pumps that require more energy to run.

Groundwater and Drought

Where is this happening? Almost everywhere. Increased demands on groundwater resources have overstressed aquifers in many areas of the world, but arid nations are particularly vulnerable because of drought.

When drought hits, agriculture is the first and most intensely affected sector. Severe drought can lead to widespread famine as well as migration of people due to its dire conditions and consequences. It can also worsen social tensions and civil unrest that are already on the rise in certain areas. (If you want to get a sense of the suffering that can come from drought, read Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath or watch a documentary on the Dust Bowl that blanketed the American Southwest during the 1930s.)

With nearly 40% of the world relying on agriculture as a primary source of income, drought threatens the livelihood of many families. It can be so severe that it reverses advancements made in reducing poverty and improving food security.

How are farmers supposed to respond during drought? Often, they drill wells deeper into the earth to tap into already dwindling groundwater, in an attempt to save high-value, water-intensive crops and livestock. But this solution, too, is short-lived. What happens when the even deeper wells run dry? We can’t keep kicking the can down the road forever.

Groundwater Pollution

Pesticides and fertilizers used in agriculture can contaminate both groundwater and surface water, as can livestock wastes, antibiotics, and processing wastes from plantation crops. For instance, manure used as fertilizer is often overapplied to fields, causing it to run off the fields and into rivers and streams.

Nitrates from agriculture are now the most common chemical contaminant in the world’s groundwater stores. Drinking water contaminated with nitrates can cause a number of health problems. It’s linked to an increased risk of blue baby syndrome, which can cause deaths in infants, as well as spontaneous abortions, and disease outbreaks traced to bacteria and viruses in waste.

Animal waste runoff from factory farms also contributes to groundwater pollution. Pathogens, like E.coli and Salmonella, are abundant in animal waste. These can run downhill during a rainstorm or seep into underground aquifers — getting into nearby water systems that spread the pathogens elsewhere.

And over the last 20 years, a new class of agricultural pollutants has emerged in the form of veterinary medicines — like antibiotics, vaccines, and growth promoters — which move from farms through the water to ecosystems and drinking water sources.

Not All Food Is Equal When it Comes to Water Consumption

When it comes to agriculture, do you know what the biggest water depleter is? It’s animal agriculture. And if there were an olympic event for the world’s biggest agricultural water waster, there’s little doubt that beef would win the gold.

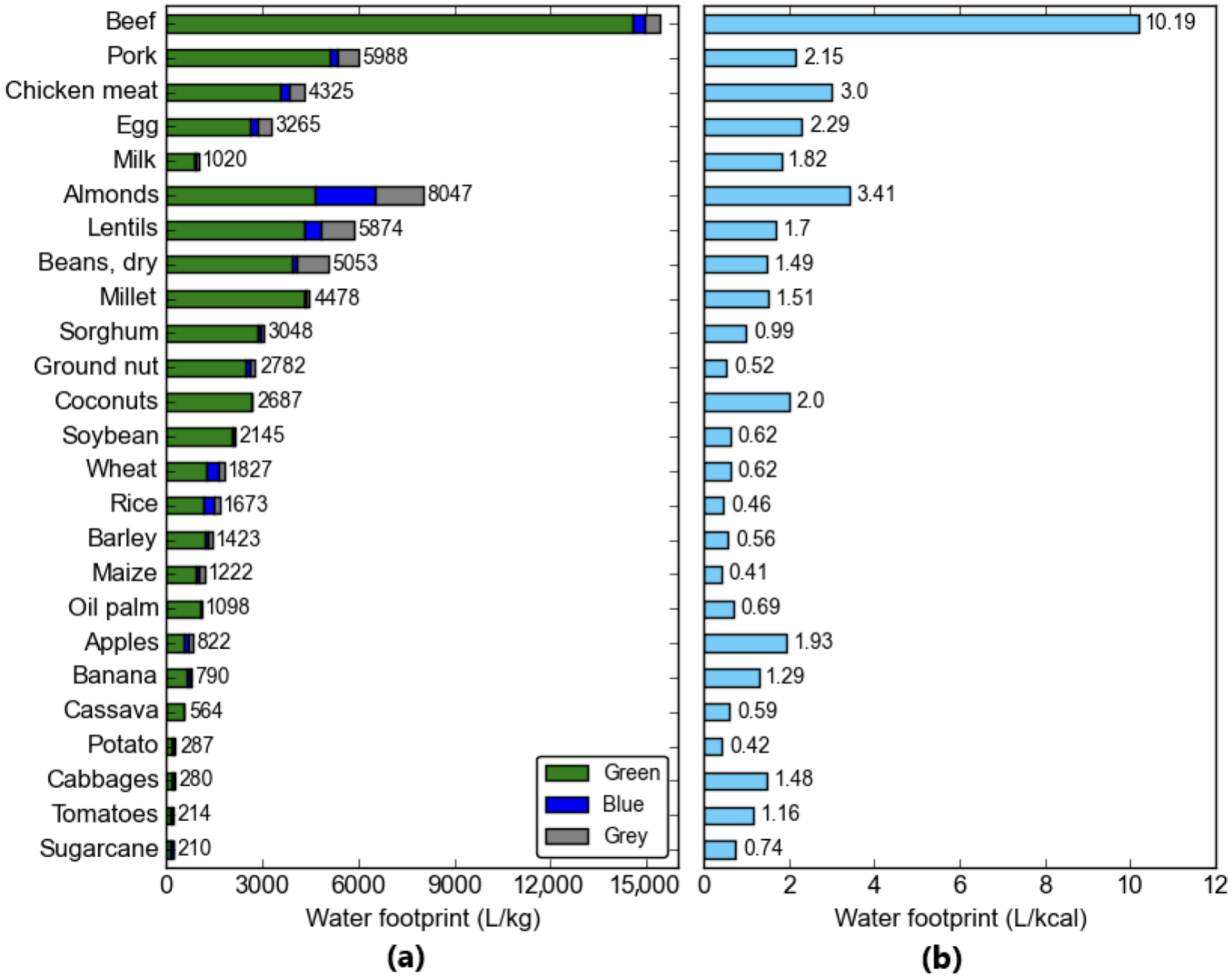

In fact, it generally takes over 20 times more water to produce a pound of beef compared to rice, grains, beans, fruits, and vegetables.

In the United States, it takes almost 1,800 gallons of water to produce a single pound of beef.

To put that in context, let’s compare that to something most of us do every day (or almost every day): showering. The average American showers for about 7.8 minutes per day, with a flow rate of 2.1 gallons per minute (lower if they have a low-flow showerhead) — thus using about 16 gallons of water showering each day. So the bottom line here is that you would save more water by not eating a pound of beef than you would by not showering for nearly four months.

This satirical video makes the point (and might make you laugh, too!):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dquV4iYt4Ds

A Protein Factory in Reverse

Why is livestock so water intensive? Are cows just really thirsty?

Sure, cows drink plenty of water. But that’s not the problem. The vast majority of the water that it takes to produce meat is used to irrigate the land that is growing their feed.

Globally, livestock production uses around 80% of the world’s agricultural land, but only provides 18% of the calories consumed by humans. And in case you were wondering, grass-fed beef has its own massive drawbacks, including the vast areas of land it requires — and whether it’s irrigated by rainfall or sprinklers. Even grassland uses large amounts of water.

With livestock, you’re getting nutrients second-hand instead of directly from the source (the plants fed to those animals). Since it takes anywhere from — depending on who is doing the calculation and what they include — four to (according to some estimates) as many as 20 pounds of grain to make a pound of feedlot-derived beef, we actually get far less food out than we put in.

It’s like a protein factory in reverse.

High-Income Countries Have The Biggest Water Impact

High-income countries like the US vastly overconsume livestock products, which puts increased pressure on water resources. And as developing countries grow their own economies and see incomes rise, their citizens also demand more “wealthy” foods like meat and dairy.

While the demand for animal products in wealthy countries in North America and Europe has remained stable over the last couple of decades, developing regions such as Asia and Latin America have seen a rapid increase in the consumption of animal products. In Brazil and China, for example, livestock farming is playing a huge role in an increasing demand for ever-more scarce supplies of water.

Case Study: California

I live in California, the most populated state in the US. Like many parts of the world, California today faces a serious water shortfall. Up to 65% of the state’s water comes from groundwater, which, in recent years, is not being replenished nearly as quickly as it’s being consumed.

California is one of the most productive agricultural regions in the world. It’s a major producer of many nuts, fruits, and vegetables, exporting more than $20B worth of these crops. It’s the only US state to export almonds, artichokes, dates, dried plums, figs, garlic, kiwifruit, olives, pistachios, raisins, walnuts, and many other critical foods.

So a drought in California is a big deal, not just to California residents like me, but to the millions of people who get their food from our fields.

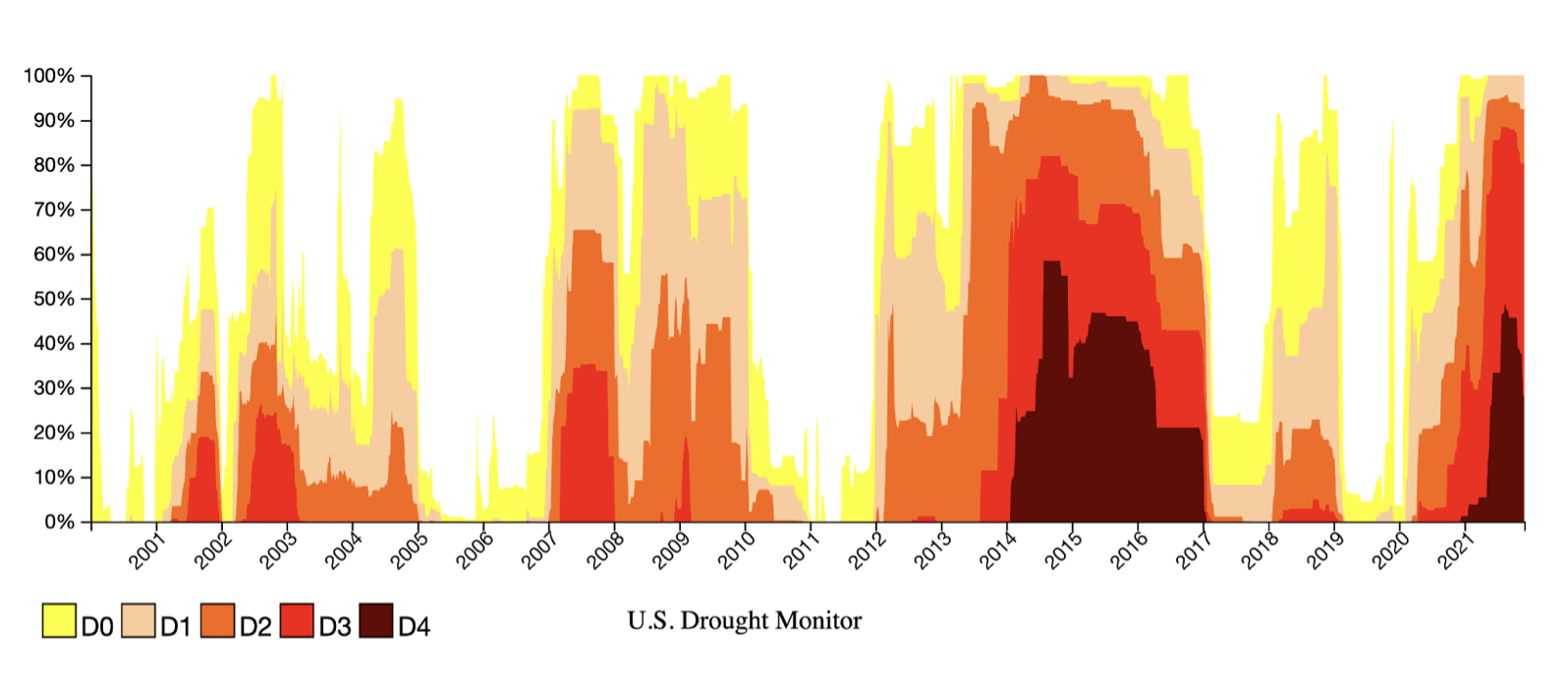

And we’ve been living in drought conditions for decades. The US Drought Monitor website shows that the weather in California has been deemed “abnormally dry” (the yellow regions in the graph below) for all but about eight months between 2000 and 2021. And the darkest region signifying “exceptional drought” lasted from 2014-2017, and returned in 2021.

The Water Impact of California’s Livestock Industry

Changing weather patterns due to climate change are at play here, for sure. But government and media calls for people to take shorter showers and replace their lawns with rock gardens — which are important steps and we should absolutely do those things — obscure the real culprits. Agriculture accounts for approximately 80% of all the water used in California. And in case you’re wondering where that water is going, specifically, consider that the state is home to at least 5.2 million cows.

Much of the production of grain and pasture crops in California feeds the state’s meat and dairy industries. Even grass-fed cattle depend on irrigation or feed imports in places with dry summers, like California, where the grass turns brown and dies before the winter rains come (if they do).

Growing hay, mostly alfalfa (which is a very thirsty crop that covers more acreage than any other crop in California), and other pastures for livestock takes at least 10 million acre-feet of water in an average year. That’s the equivalent of a quarter of an acre, covered a foot-deep in water, for every citizen of the state. And much of California’s alfalfa is being shipped to countries like China and Saudi Arabia, for them to feed to their livestock.

At a certain point, you have to wonder: what’s wrong with this picture?

Californians are being told to flush the toilet less often, and to take shorter showers. They’re giving up lawns, and in some cases, even vegetable gardens. But California’s livestock industry alone uses more water than all the homes and businesses in the state combined. And even with all that water, California still imports most of the meat consumed in the state.

Reducing Water Scarcity Through Diet

So what can you do about agricultural water usage? Changing your diet can reduce water scarcity in some of the hardest-hit places, by helping to replace water-intensive animal agriculture with water-wise fruits, veggies, legumes, seeds, and whole grains. Diets that consider sustainability, as well as animal welfare and individual health, can reduce water consumption and help make the world a better place.

1. Swap Beans for Beef

One of the most common recommendations to improve the sustainability of your diet is the alliterative act of swapping beans for beef. This shift highlights a general principle: swapping plant-based foods for animal-based foods, thus eliminating the middleman (or middlecow, as the case may be). Instead, you get your nutrients directly from the source. This is one of the most impactful lifestyle changes you can make in the service of global sustainability and water conservation.

2. Try Meat and Dairy Alternatives

If you’re totally new to the idea of eating more plant foods, you can use plant-based meat and dairy analogs — like the Beyond Burger, for example — to become more comfortable eating this way. These are so similar to their animal-derived counterparts in taste and texture that many meat eaters and non meat eaters alike can’t tell the difference.

According to the UN, these types of meat substitutes use up to 99% less water, up to 95% less land, and generate up to 90% fewer harmful emissions than regular beef burgers, while consuming about half the energy.

That’s a great start, for sure. But at the end of the day, these foods are still processed. And the healthiest diets for most people are those primarily based on whole plant foods.

3. Choose Plants to Fill Your Plate

Overall, the foods with the lowest water usage are vegetables, fruits, and cereal grains. Pulses — or beans, peas, and lentils — are mid-range in terms of water usage, and nuts and seeds are higher. But any of these categories are still a vastly better choice than meat or dairy products. If you want to save water, reducing industrialized beef consumption could be the most powerful single step you can take.

For crops grown specifically in California, where I live, the foods that use the least amount of water are:

- Asparagus

- Apples

- Hot Peppers

- Cabbage

- Cauliflower

- Beans

- Grapefruit

- Onions

- Pears

- Potato

- Raspberry

- Sweet Potato

- Tomatoes

- Blueberries

This chart from a 2020 article in the journal Water, shows a visual representation of the water footprints of various foods. These numbers are based on the water footprint of a liter of water per kg of product (a) and the water footprint of a liter of water per kcal of nutritional energy (b).

What About Almonds?

This isn’t an idle question, since the demand for almond products continues to be on the rise. The largest almond producer in the world is California, where the number of almond orchards has doubled over the last two decades.

One of the most common arguments against choosing plant-based milk products, like almond milk, over dairy products is that almonds are still water intensive. And there’s some truth to that. A single almond takes 1.1 gallons of water to produce, or approximately 10 gallons per handful. One reason for this is that almond trees require water year-round, even when they’re not producing nuts.

Before you start slapping an “Almonds are Evil” bumper sticker on your car, let’s put those numbers in perspective. While almonds may not be the most sustainable crop around, almond milk still uses less water, overall, than cow’s milk. And on the whole, they’re a substantial improvement over the footprints of animal agriculture. (For our article on plant-based milks, click here.)

Further Ways to Reduce Your Food and Water Footprint

If you’re wondering how to change your diet to become less water intensive, I applaud you for being willing to examine your personal choices in this way.

The world is shaped, in part, by the choices that each of us makes, every single day. When you bring your food choices into alignment with your values, you contribute to building a healthier world for future generations. It may be only a drop in the bucket, but when it comes to water, every drop really does count.

The #1 thing you can do is to eliminate — or at least reduce — your consumption of animal products; especially those, like beef and dairy products, that come from cows. Instead, shift your diet to one that’s more focused on whole plant foods. This also means getting most of your protein from plant foods, which includes things like beans, peas, lentils, nuts, seeds, soy (go organic to steer clear of GMOs), and grains.

Additionally, making strides to eat locally grown foods whenever possible is a great way to support the environment as well as your health. For instance, try a CSA or a U-Pick farm in your area. This both reduces the environmental footprint of your food and supports your local farmers.

To make things even more local, you might consider starting your own food garden. And if you have some land, practice permaculture principles, like rainwater catchment, berms, and swales, to make use of the water that comes to you, and help it go into the soil instead of running off into rivers.

Your Food Choices Can Help Save the Planet

Meat and dairy production has by far the largest water footprint of any human activity. As demand for animal products increases worldwide, stress on increasingly limited groundwater supplies also increases, threatening the ability of future generations to be able to grow food at all. Reducing or eliminating animal product consumption could be the #1 thing you can do to minimize your water footprint. By adopting a more plant-based diet full of whole, organic, and local plant foods, you can vote with your dollars for a healthier, ethical, and more sustainable world for us all.

Tell us in the comments:

- What’s one thing you learned from this article?

- Do you live in an area that has been affected by drought? How has this impacted your food choices and lifestyle?

- What’s one thing you can do to make your diet more sustainable in terms of water consumption?

Feature Image: iStock.com/AkarawutLohacharoenvanich