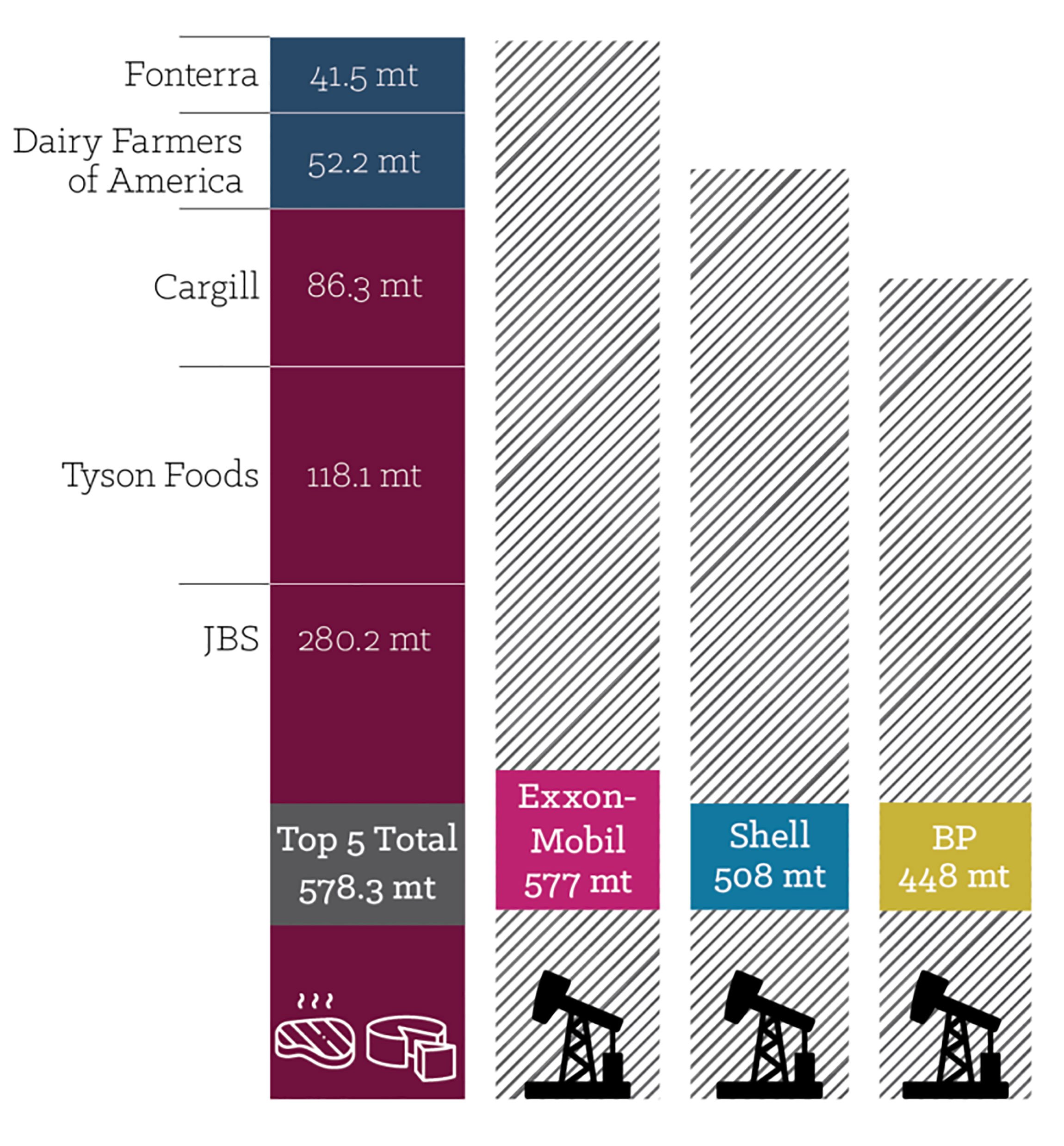

New research shows that together, the world’s top five meat and dairy corporations are responsible for more annual greenhouse gas emissions than ExxonMobil, Shell, or BP.

By H. Claire Brown • Originally published on NewFoodEconomy.org

The New Food Economy is a non-profit newsroom covering the forces shaping how and what we eat. Read more at newfoodeconomy.org.

A study released on July 18, 2018, found that the world’s top five meat and dairy producers combined — Brazil’s JBS, New Zealand’s Fonterra, Dairy Farmers of America, Tyson Foods, and Cargill — emit more greenhouse gases than Exxon-Mobil, Shell, or BP.

Here’s another way to look at it: If these meat and dairy companies continue to grow based on current projections, by 2050 they will be responsible for 81% of global emissions targets.

Emissions Impossible: How Big Meat and Dairy Are Heating Up The Planet

The report, released by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) and the international nonprofit GRAIN, bases its calculations on a method of accounting that includes the entire supply chain.

Rather than stop at milk trucks and processing plants, the authors argue, a full account of emissions from meat and dairy should also include energy used in manufacturing fertilizer and growing the animals’ feed. These supply-chain emissions can account for 80 to 90% of the total energy it takes to put a bottle of milk on the shelf.

“It’s widely accepted that you can’t be a company operating in a sector where the products you’re selling are responsible for huge amounts of emissions without considering that the impact is part of your own,” says study author Devlin Kuyek.

He compares meat companies that calculate emissions without including livestock feed to Exxon claiming it’s responsible only for its oil rigs and refineries, and not the greenhouses gases released into the atmosphere once its gas is burned.

According to the report, half of the top 35 meat and dairy companies don’t publicly release any emissions numbers, and the ones that do are all over the place. JBS, the largest livestock producer in the world, claims its calculations include the entire supply chain. But when the researchers checked the company’s numbers against a system established by the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (UNFAO), they found that JBS’s estimates came in at just 3% of the independent evaluation.

Cargill and Tyson don’t include supply-chain emissions in their public reporting or reduction targets, and just six of the top 35 meat and dairy companies have publicly announced plans to reduce emissions along the supply chain.

An Existential Problem in Meat and Dairy Production

Calculations aside, Kuyek says the report illuminates an existential problem in meat and dairy production: These companies envision a world where per-capita consumption continues to rise. They’re ramping up exports, lobbying legislatures, and pushing for deregulation in the name of more meat for more people, yet those targets are fundamentally at odds with a changing climate.

In 2014, JBS predicted global meat consumption would hit 105 pounds per person by 2030, up 30% from 81 pounds per person in 1999 — great news for the beef business.

By contrast, Greenpeace estimates global per-capita meat consumption actually has to fall to 35 pounds per person by 2050 to meet goals set by the Paris Climate Agreement, which the United States withdrew from in August of 2017.

The Tysons of the world shouldn’t be trusted to pursue unfettered growth and meaningful emissions reductions in equal measure, the authors argue. That means governments will have to intervene.

“There should be really a clear directive and policies and regulations that create a food system in which there is production of enough meat to eat — moderate consumption levels for everyone. And that can provide dignified remuneration to the farmers and good working conditions for workers in the industry. That should be something that companies should have to comply with,” Kuyek says.

What If Governments Limited The Amount of Meat and Dairy Companies Could Produce?

It sounds so crazy it just might work. Kuyek lives in Canada, and he’s seen a successful version of this approach to regulation firsthand.

Canada’s dairy farmers operate under a system called supply management, which means the government sets production quotas and farmers aren’t allowed to produce more than their allotment.

He calls it a “pretty fair system,” adding that governments could consider environmental goals when setting quotas for milk and dairy. President Trump and other world leaders have called Canada’s dairy policy protectionist because the success of supply management depends in part on maintaining high tariffs on dairy imports.

Yet in the U.S., a cheese surplus the size of the U.S. capitol building and a struggling dairy industry have prompted some farmers to advocate for a return to the supply-management system that also governed this country’s producers until the late 20th century.

As the Food and Environment Reporting Network’s (FERN) Leah Douglas reported in May, the country’s largest dairy co-op is discussing the possibility of coming out in support of supply management. Though it was largely dismissed as an outdated policy for many years, support for supply management may be edging its way back into the mainstream.

The meat industry has never worked under quotas, and the few corporations that control the vast majority of meat production in this country would likely fight tooth and nail to avoid caps on growth. But Kuyek argues they’ll never reduce production voluntarily — and that improvements to productivity and efficiencies won’t do the trick, either.

“We have a major problem in the growth strategies of these companies — emphasis on exports and overproduction,” he says. “There’s no way it would be possible to achieve our objectives if we’re not making some serious changes in the way the system functions.”

Editor’s Note: After receiving feedback from our community, we changed the title of the article, and we apologize for any confusion. We want to clarify that this article is suggesting that the combined greenhouse gas emissions of the top five meat and dairy companies are on par with the emissions of ExxonMobil and are significantly higher than those of Shell or BP.

The point remains: The industrial livestock and dairy corporations are contributing significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. In fact, as the report shows, the combined emissions of the top 20 meat and dairy companies surpass the emissions from entire nations, such as Germany, Canada, Australia, or the United Kingdom! Most of these companies aren’t reporting their emissions accurately, and many aren’t taking adequate steps to reduce emissions.

Even more, large meat and dairy companies are pushing more production. If the growth of the global meat and dairy industry continues as projected, by 2050, the livestock sector as a whole could contribute 80% of the planet’s annual greenhouse gas budget (set by the 2015 Paris climate agreement).

At Food Revolution Network, we believe the movement for healthy, ethical, and sustainable food invites action from all stakeholders — including consumers, food producers, medical providers, and governments. This article suggests that government could have a role to play in reducing global production of animal products and that this could have significant impacts on our global climate.

Tell us in the comments:

-

What do you think? Does humanity need to reduce production of animal products if we are to achieve environmental sustainability?

-

Is there a role government could play in that, and if so, what do you think it should be?

-

Does the environmental impact of animal products influence how much (or little) animal products you consume? Or where you source them from?